Cellular respiration and photosynthesis are vital processes, intricately linked in bioenergetics, powering life through energy transformations and crucial macromolecule connections.

Overview of Bioenergetics

Bioenergetics explores the fascinating transformations of energy within living organisms. It’s the study of how organisms acquire, store, and utilize energy to perform life’s functions. Central to this is understanding ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the primary energy currency of cells, fueling processes like muscle contraction and nerve impulse transmission.

Photosynthesis and cellular respiration represent complementary sides of the same energetic coin. Photosynthesis captures light energy to build glucose, storing energy within its chemical bonds. Conversely, cellular respiration breaks down glucose, releasing that stored energy as ATP. This cyclical relationship highlights the fundamental principle of energy flow through ecosystems, demonstrating how energy isn’t created or destroyed, but rather converted from one form to another.

The Interdependence of Photosynthesis and Cellular Respiration

Photosynthesis and cellular respiration are fundamentally linked in a reciprocal relationship, forming a continuous cycle of energy and matter. Photosynthesis utilizes carbon dioxide and water, releasing oxygen as a byproduct, while cellular respiration consumes oxygen and produces carbon dioxide and water.

Essentially, the products of one process serve as the reactants for the other. This interdependence sustains life on Earth, maintaining atmospheric balance and providing the energy necessary for all living organisms. Plants, through photosynthesis, create the glucose and oxygen that heterotrophs (like animals) rely on for cellular respiration. In turn, animals release the carbon dioxide needed by plants for photosynthesis, completing the cycle.

Photosynthesis: Capturing Light Energy

Photosynthesis converts light energy into chemical energy, fueling ecosystems; it’s a complex process occurring within chloroplasts, vital for producing oxygen and glucose.

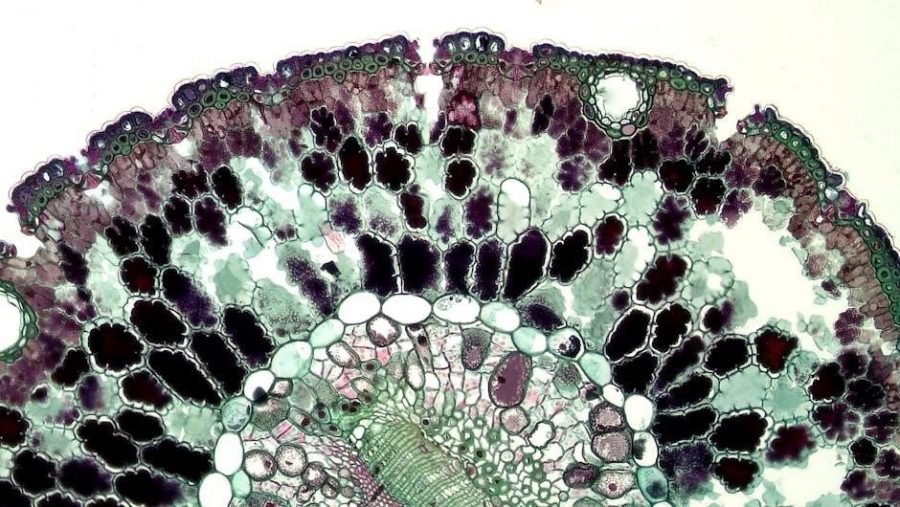

Chloroplast Structure and Function

Chloroplasts, the sites of photosynthesis, possess a unique structure optimized for capturing light energy. These organelles are enclosed by a double membrane – an outer and inner membrane – creating distinct compartments; Within the chloroplast lies the thylakoid membrane, arranged in flattened sacs called thylakoids, often stacked into structures known as grana.

The space surrounding the thylakoids is the stroma, a fluid-filled region where the Calvin cycle takes place. Chlorophyll, the pigment responsible for absorbing light, is embedded within the thylakoid membranes. This compartmentalization allows for efficient light capture and subsequent conversion into chemical energy. The chloroplast’s structure directly supports its function in transforming light energy into sugars, providing the foundation for most food chains on Earth.

Light-Dependent Reactions

Light-dependent reactions occur within the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts, initiating photosynthesis with light absorption. This energy drives the splitting of water molecules (photolysis), releasing oxygen as a byproduct and providing electrons. These electrons move through an electron transport chain, generating a proton gradient used to synthesize ATP via chemiosmosis – a process mirroring that in mitochondria.

Simultaneously, light energy is used to reduce NADP+ to NADPH, another energy-carrying molecule. Both ATP and NADPH, produced during these reactions, are crucial for powering the subsequent light-independent reactions (Calvin cycle). Essentially, light energy is converted into chemical energy stored in ATP and NADPH, preparing it for sugar synthesis.

Photosystems I and II

Photosystem II (PSII) captures light energy, initiating the light-dependent reactions by oxidizing water to release electrons, protons (H+), and oxygen. These electrons enter an electron transport chain. Photosystem I (PSI) receives electrons from the transport chain and re-energizes them with additional light absorption.

PSI then uses these high-energy electrons to reduce NADP+ to NADPH. Both photosystems contain chlorophyll and other pigment molecules that absorb light at different wavelengths, maximizing light capture. The sequential action of PSII and PSI ensures efficient electron flow and energy conversion. They work in tandem, converting light energy into the chemical energy stored in ATP and NADPH, essential for the Calvin cycle.

Light-Independent Reactions (Calvin Cycle)

The Calvin cycle, occurring in the stroma of chloroplasts, utilizes the ATP and NADPH generated during the light-dependent reactions. It begins with carbon fixation, where CO2 combines with RuBP, catalyzed by RuBisCO. This unstable six-carbon compound immediately breaks down into two molecules of 3-PGA.

Next, in the reduction phase, ATP and NADPH convert 3-PGA into G3P, a three-carbon sugar. Some G3P exits the cycle to be used for glucose and other organic molecule synthesis. Finally, regeneration uses ATP to convert remaining G3P back into RuBP, allowing the cycle to continue. For every six CO2 molecules fixed, one glucose molecule is produced, demonstrating the cycle’s crucial role in sugar creation.

Carbon Fixation, Reduction, and Regeneration

Carbon fixation initiates the Calvin cycle, where atmospheric CO2 is incorporated into an organic molecule – RuBP – with RuBisCO’s assistance. This forms an unstable intermediate, swiftly dividing into two 3-PGA molecules. The reduction phase then employs ATP and NADPH to convert 3-PGA into G3P, a sugar precursor. This step requires energy and reducing power from the light-dependent reactions.

Crucially, only a fraction of G3P is net gain; the rest fuels regeneration of RuBP, ensuring the cycle’s continuation. This regeneration demands additional ATP. These three phases – fixation, reduction, and regeneration – operate in a continuous loop, ultimately converting inorganic CO2 into usable organic compounds, forming the foundation for most ecosystems.

Cellular Respiration: Releasing Chemical Energy

Cellular respiration breaks down glucose, releasing stored energy as ATP, utilizing glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation within mitochondria.

Mitochondrial Structure and Function

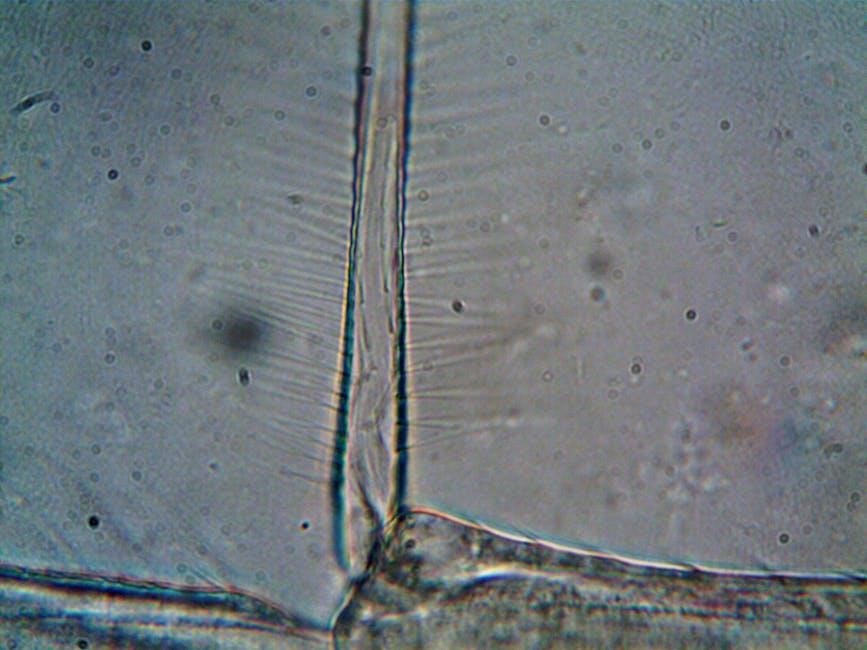

Mitochondria, often called the “powerhouses of the cell,” are double-membrane bound organelles central to cellular respiration. Their outer membrane is smooth, while the inner membrane is highly folded into cristae, increasing surface area for ATP production.

The space within the inner membrane is the mitochondrial matrix, containing enzymes for the citric acid cycle and other metabolic processes. Intermembrane space, between the membranes, plays a crucial role in chemiosmosis.

These structures facilitate the efficient breakdown of nutrients to generate ATP, the cell’s primary energy currency. The compartmentalization within the mitochondria optimizes each stage of cellular respiration, maximizing energy yield and supporting life’s processes.

Glycolysis: Breaking Down Glucose

Glycolysis, occurring in the cytoplasm, is the initial stage of cellular respiration, breaking down one molecule of glucose into two pyruvate molecules. This anaerobic process doesn’t require oxygen and yields a small net gain of ATP (2 molecules) and NADH.

The process involves ten enzymatic reactions, divided into two phases: the energy-investment phase (consuming ATP) and the energy-payoff phase (producing ATP and NADH).

Pyruvate, the end product, then enters the mitochondria (in aerobic conditions) for further processing. Understanding glycolysis is fundamental, as it sets the stage for subsequent stages, linking photosynthesis’s products to energy production within the cell.

Pyruvate Oxidation and the Citric Acid Cycle

Pyruvate oxidation, a crucial link between glycolysis and the Citric Acid Cycle (Krebs cycle), transforms pyruvate into Acetyl CoA, releasing carbon dioxide and generating NADH. This process occurs in the mitochondrial matrix.

The Citric Acid Cycle itself is a series of eight reactions that further oxidize Acetyl CoA, releasing more carbon dioxide, ATP, NADH, and FADH2. These electron carriers (NADH and FADH2) are vital for the next stage – oxidative phosphorylation.

The cycle regenerates its starting molecule, ensuring continuous operation. Understanding these steps is key to grasping how the energy initially captured during photosynthesis is fully extracted and prepared for ATP synthesis.

Oxidative Phosphorylation: Electron Transport Chain and Chemiosmosis

Oxidative phosphorylation, the final stage of cellular respiration, comprises the Electron Transport Chain (ETC) and chemiosmosis. The ETC, located in the inner mitochondrial membrane, uses electrons from NADH and FADH2 to pump protons (H+) into the intermembrane space, creating a proton gradient.

This gradient represents potential energy, harnessed by chemiosmosis. Protons flow down their concentration gradient through ATP synthase, an enzyme that uses this energy to phosphorylate ADP, forming ATP.

Oxygen serves as the final electron acceptor, forming water. This process generates the vast majority of ATP produced during cellular respiration, effectively converting the energy from glucose into usable cellular fuel.

Role of ATP Synthase

ATP synthase is a remarkable enzyme central to oxidative phosphorylation and, consequently, efficient cellular respiration. Embedded within the inner mitochondrial membrane, it functions as a molecular turbine, utilizing the proton (H+) gradient established by the electron transport chain.

As protons flow down their concentration gradient through ATP synthase, the enzyme rotates, binding ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) to form ATP. This process, called chemiosmosis, directly couples the proton motive force to ATP synthesis.

Essentially, ATP synthase converts the potential energy stored in the proton gradient into the chemical energy of ATP, the primary energy currency of the cell, powering numerous cellular processes.

Comparing and Contrasting Photosynthesis and Cellular Respiration

Photosynthesis builds sugars using light energy, while cellular respiration breaks them down to release energy, showcasing complementary, yet opposing, bioenergetic pathways.

Reactants and Products

Photosynthesis utilizes carbon dioxide and water, absorbing light energy to produce glucose and oxygen as vital products; this process essentially stores energy within the glucose molecule. Conversely, cellular respiration consumes glucose and oxygen, breaking down these reactants to release energy in the form of ATP, alongside carbon dioxide and water as byproducts.

These reactions are fundamentally reciprocal. The products of photosynthesis—glucose and oxygen—serve as the primary reactants for cellular respiration, while the products of respiration—carbon dioxide and water—are essential for photosynthesis. This cyclical exchange demonstrates a crucial interdependence, highlighting how these processes sustain life by continuously converting and utilizing energy and matter within ecosystems.

Energy Flow and Transformation

Photosynthesis captures light energy, transforming it into chemical energy stored within the bonds of glucose. This represents an endothermic process, requiring energy input. Conversely, cellular respiration releases the chemical energy from glucose, converting it into a usable form – ATP – through an exothermic process.

Energy flow isn’t perfectly efficient; some energy is inevitably lost as heat during each transformation, adhering to the laws of thermodynamics. This energy isn’t destroyed, but becomes less available for biological work. The transfer of energy between these processes fuels all life activities, from plant growth to animal movement, demonstrating a fundamental principle of bioenergetics and ecosystem function.

Factors Affecting Photosynthesis and Respiration

Environmental conditions, like light intensity, carbon dioxide levels, and temperature, significantly impact both photosynthetic rates and the efficiency of cellular respiration.

Limiting Factors in Photosynthesis

Photosynthetic efficiency isn’t limitless; several factors can constrain the rate at which plants convert light energy into chemical energy. Light intensity is paramount – as light increases, photosynthesis generally rises, but only to a certain point. Beyond that, it plateaus, and excessive light can even damage the photosynthetic machinery.

Carbon dioxide concentration also plays a critical role. While often abundant, CO2 levels can become limiting, especially in enclosed environments. Increasing CO2 boosts photosynthesis, again up to a saturation point. Temperature is another key regulator; enzymes involved in photosynthesis have optimal temperature ranges. Too cold, and reactions slow; too hot, and enzymes denature, halting the process.

Water availability, though less direct, impacts photosynthesis by influencing stomatal opening and CO2 uptake. A deficiency causes stomata to close, restricting CO2 entry and slowing down the entire process.

Environmental Impacts on Respiration

Cellular respiration, while fundamental, isn’t immune to environmental influences. Temperature significantly affects respiration rates; higher temperatures generally increase metabolic activity, boosting respiration, but exceeding optimal ranges can denature enzymes and halt the process. Conversely, lower temperatures slow respiration down.

Oxygen availability is crucial, as it serves as the final electron acceptor in aerobic respiration. Reduced oxygen levels, like those at high altitudes or in waterlogged soils, limit respiration and can force cells to switch to less efficient anaerobic pathways like fermentation.

Water availability indirectly impacts respiration. Water stress can lead to stomatal closure, reducing photosynthesis and subsequently, the supply of glucose for respiration. Furthermore, the metabolic cost of maintaining cellular function under water stress increases respiratory demand.

Alternative Metabolic Pathways

Fermentation and other anaerobic processes offer energy production when oxygen is scarce, connecting to carbohydrate metabolism and providing vital cellular energy reserves.

Fermentation: Anaerobic Respiration

Fermentation pathways allow for ATP production without oxygen, crucial when cellular respiration is limited. These processes regenerate NAD+, essential for glycolysis to continue, albeit with a significantly lower energy yield compared to aerobic respiration.

Two primary types exist: lactic acid fermentation, common in muscle cells during intense activity, and alcoholic fermentation, utilized by yeasts and some bacteria. Lactic acid fermentation converts pyruvate to lactate, while alcoholic fermentation yields ethanol and carbon dioxide.

While less efficient, fermentation is vital for organisms in oxygen-deprived environments and has significant applications in food production – think yogurt, cheese, and brewing. Understanding fermentation highlights the adaptability of metabolic pathways to varying conditions.

Connections to Macromolecules (Carbohydrates, Lipids, Proteins)

Macromolecules serve as the primary fuel sources and building blocks for both photosynthesis and cellular respiration; Carbohydrates, like glucose, are directly utilized in glycolysis, providing initial energy for respiration and originating from photosynthesis.

Lipids, stored as fats, offer a more concentrated energy reserve, yielding more ATP upon breakdown. Proteins can be broken down into amino acids, entering respiration pathways when carbohydrate and lipid stores are depleted.

Photosynthesis, conversely, utilizes carbon dioxide to synthesize carbohydrates, effectively storing energy. These interconnected pathways demonstrate how organisms cycle energy and matter, linking macromolecule metabolism to fundamental life processes.